Mavericks + Music: Black Cowboy Culture Dominates Music Charts, Mainstream

May 17, 2019

She sashays into the dirt-filled arena. Flanked by young, black cowboys Devinn Jordan, 26, and Mazi Willis, 24, atop stately steeds, veteran rapper and singer Khia Thug Misses hikes up the front of her black, ruffled Western dress. She gives a little leg. Props a hand on her hip. “Y’all ready to cut up with Cowgirl Khia Shamone?” she asked, followed by a burst of hearty laughter. “I’m ready to shoot.”

Cowboys and cowgirls posted along the arena fence respond with chuckles and claps as Khia strikes a pose in front of her not-so-average crowd. And like that, hip hop, country Western fashion and cowhand culture collide. The occasion continues a music industry trend currently cross-pollinating the nation: artists from the two genres collaborating to pay homage to black cowhands and their contributions to the American West.

“The black cowboy is tough,” said professional bareback rider and black Indian Billy Ray Thunder, 65, of Atlanta. “Being one in the sports world wasn’t popular on the East Coast because of how dangerous the sport is, but I hope we see more young people come into the industry to keep it alive. Our story is an important one.”

Khia joined Thunder and almost a dozen other cowhands of color from around the Atlanta area for an early May day of Southern storytelling, fellowshipping and a rodeo-inspired photo shoot at Ellenwood Equestrian Center in Ellenwood, Georgia. Roughly 25 minutes south of the metro limits.

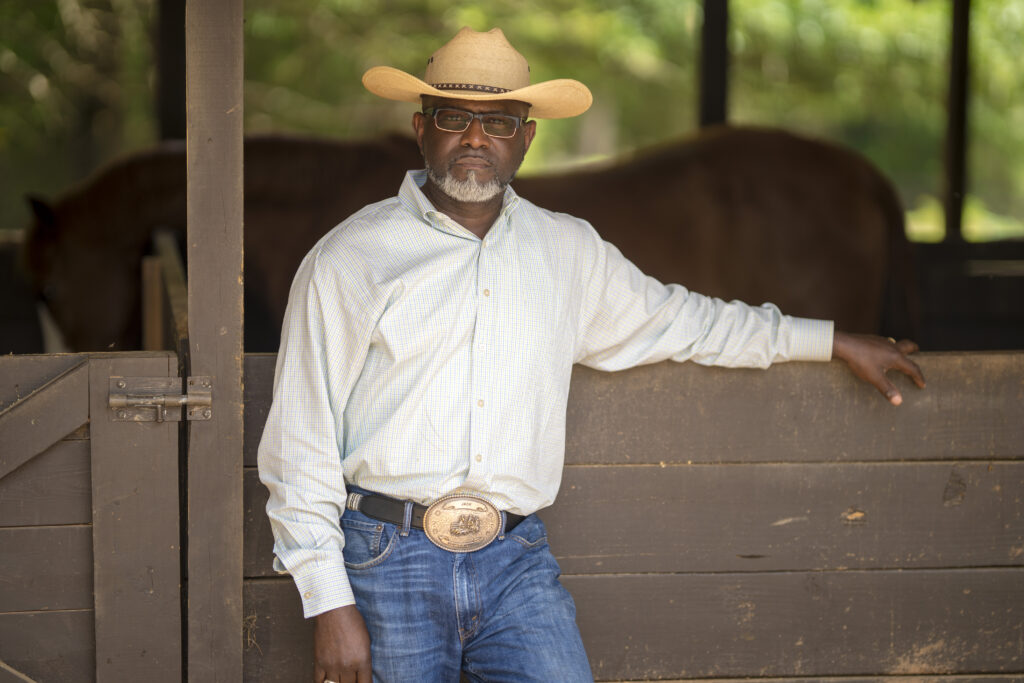

“I came out to support our culture and for my love of music,” said Ron Parker, a 66-year-old black cowboy from Conyers and drummer who occasionally rocks out with Parliament Funkadelic. “I have accepted that the music has changed from what I’m used to. Sometimes I don’t have a clue what they’re saying, but it’s great to see all of us come together to celebrate us and our history.”

Atlanta-based rapper and singer Khia Thug Misses posing with veteran Black cowboys Ron Parker and Billy Ray Thunder. Photo by Trarell Torrence

Black cowboys permeating pop culture, music charts

Professional drummer Ron Parker performs for legendary bands like Parliament Funkadelic and is a lifelong cowboy sustaining Black West history. Photo by Trarell Torrence

More recently, hip hop and R&B stars have become even more inspired by frontier fashion and Old West lifestyles. As a result, the historical connection between cowboy culture and people of color has strengthened with the masses. Through music videos and live concerts, artists are now experiencing trailblazing achievements in entertainment — just by inserting blacks back into the American West storyline (a narrative African-American cowhands helped originate in the first place).

“The funny thing is,” said Khia, an Atlanta resident and avid horseback rider for more than a decade now, “country-Western culture has been part of my life since I was a kid. I grew up in rural parts of both Mississippi and the Carolinas with my grandparents and parents. Making mud pies, drinking lemonade on the front porch and getting dirty on the land was normal.” Like Khia, the following pop culture personalities have challenged traditional notions of the American white cowboy image in entertainment and earned Wild West success:

2019: Atlanta rapper Lil Nas X’s country/rap single “Old Town Road” has topped the Billboard Hot 100 as the No. 1 hit since April. During March, it climbed the global Apple Music and the Spotify United States Top 50 charts. The remix version features country singing vet Billy Ray Cyrus; however, it received lackluster acclaim within the country Western community. The song also made the Billboard Hot Country Songs chart but was pulled because of a “mistake.”

A veteran bull rider and bareback competitor, Bill Ray Thunder is known in the Black rodeo community as “The Living Legend.” Photo by Trarell Torrence

California rapper Tyga dropped hip hop/country Western track “Goddamn” mid-April and has since created a summer banger buzz. The video shows white cowboys and cowgirls slumped in saloon boredom until Tyga and his posse (primarily cowhands of color) step onto the scene to liven up the place. New York rapper Cardi B performed at the Houston Livestock Show and Rodeo during March. She broke the paid rodeo attendance count, beating country singer Garth Brooks’ closing 2018 performance. Cardi B’s 75,580 show supporters bumped her into the all-time paid attendance record. She stunned wearing a pink and baby blue fringed and chaps outfit.

2018: Virginia Beach rapper Lil Tracy teamed up with Philadelphia rapper Lil Uzi Vert to remix “Like a Farmer” — an unlikely hick-hop anthem. Its popularity online came by way of Twitter. Footage of rodeo participants trying to dance to the lyrics went viral.

2017: Atlanta rapper/singer Young Thug collaborated with London singer Millie Go Lightly for “Family Don’t Matter.” The country rap duo gave opposite music genres a new, dreamy twist. The song’s video showed off the rapper’s horseback riding skills and reinforced black, country love as Young Thug trots across the countryside to woo his dream woman.

2016: Houston superstar Beyoncé performed her country Western-influenced song “Daddy Lessons” at the Country Music Association Awards. The awards became a first-time appearance for Beyoncé, who also graced the stage with the legendary trio The Dixie Chicks for the event. The song and performance were considered Queen Bey’s first real push into country music.

2015: Khia’s classic 2002 hit, “My Neck, My Back,” became part of New York City’s Adult Swim Upfront Party when pop and country singer Miley Cyrus—Bill Ray Cyrus’ daughter—included the track in her set. Khia acknowledged Miley on Twitter by saying: “Damn Shame It Took A Sweet Country White Chic To Pay Homage To The Queen!! (sic)” And the list goes back for decades.

Black cowboys pioneering country music

Cowboy Jerome Lawrence is a modern-day Buffalo Soldier with a deep appreciation for Black cowhand and Old West history. Photo by Trarell Torrence

The recent controversy of Lil Nas X’s snatched song from the Billboard country chart has reaffirmed country music’s historical difficulty with the inclusion and acceptance of black artists. “Lil Nas helped put us black cowboys on the map again in rap and country music,” said Jordan, an Atlanta horse trainer and bull rider. “For me, it’s more than the music, though. It’s hard work. Being a real cowboy has opened up so many doors for me as a young businessman and rodeo competitor.”

Black cowhands carry mysticism and misconception concerning their role in the development of the American West. “Many people feel the cowboy is uniquely American in dress, lifestyle and attitude, and represents the best aspect of ourselves,” said Michael “Cowboy Mike” Searles, a black cowboy historian, author and retired assistant professor of history from Augusta University. “For most Americans, the black cowboy does not exist. There is a certain romance with the West, the western lifestyle and the notion that we stood toe to toe with white cowboys. In some cases, bested them brings joy to our hearts.”

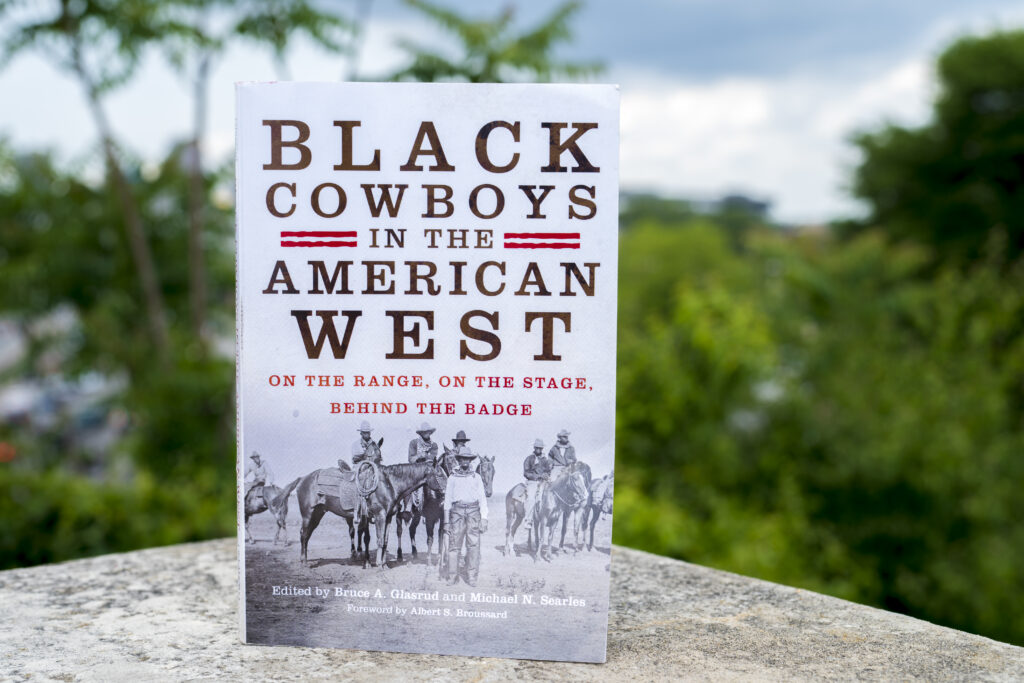

Searles co-edited the scholarly book, “Black Cowboys in the American West: on the range, on the stage, behind the badge.” The book reveals that, contrary to pop culture depictions and lack of recognition by white America, there were at least 5,000 black cowboys who worked during the 19th century. Their Old West roles ranged from singers, fiddlers, cattlemen and cowpunchers to foremen, bronco busters, bulldoggers, drovers, ropers, cooks and brand readers.

“Our culture and history is sacred and one we fight hard to preserve,” said Jerome Lawrence, 55, a black cowboy, Buffalo Soldier and assistant head chaplain for Fulton County Sheriff’s Office. “Just as much as the music has been influential for some, knowing our past and that we demonstrated remarkable horsemanship in those American West days has been a huge part of my ministry to reach and teach the younger generations.”

Co-edited by Georgia-based historian Michael Searles (a.k.a. Cowboy Mike) ‘Black Cowboys in the American West’ is a collection of previously published articles and new research that surveys the work, life and influence of black cowboys before and after the Civil War. Photo by Trarell Torrence

“Black Cowboys in the American West” mentions that the musical traditions of African-American cowboys were virtually undocumented before and after the Civil War. Yet, oral stories from the 20th century confirmed black ranch hands gravitated more toward blues and church hymns as forms of “cowboy songs.” A distinguishing style called “black cowboy blues.”

“Many whites and some blacks feel that country music belongs exclusively to white folks,” said Searles. “This does not comport with the fact that many blacks grew up listening to, singing, writing and performing country music. Take DeFord Bailey for example. He was a pioneer not only for African-American country singers — but for all country musicians.”

A world-class harmonica player, Bailey was the first country singer from the 1920s until the 1940s who was introduced on the Grand Ole Opry. Not just the first black country singer either, the first-ever country musician. Opry founder George Hay made the announcement live on air Dec. 10, 1927. However, not every black person has been happy when a black artist moved into the country genre, Searles pointed out.

“Ray Charles was thought to be off track by some when he recorded ‘Modern Sounds in Country and Western Music’ in 1962,” he said. “We live in a world that’s divided off between white and black; urban and rural; and young and old. A number of whites were not pleased to discover that country music star Charley Pride was black. Some black folk felt Elvis Presley was stealing our music.”

When traditional styles of music are modified, hostile reactions follow. It’s like blasphemy to “true” country music fans when country music merges with rap, Searles said. “The folks who own the Billboard charts are mindful of the fans who make these charts valuable,” he said. “If there is a resistance to who appears on the charts, they respond. In time, country/Trap songs will be accepted as just another form of country music. Acceptance will grow as more movies are made, stories are written and songs are recorded.” Searles stressed that exposure is critical to changing attitudes. “Before the election of Barack Obama, people could not imagine a black president,” he said. “Today, that notion is no longer farfetched.”

Ellenwood Equestrian Center

Owned and operated by mother-daughter pair Lynn and Leah, Ellenwood Equestrian Center (EEC) is a nearly 20-acre riding school, camp venue and dressage training barn. “We run one of the biggest equestrian programs around the Atlanta area,” said Lynn. “About 50 percent of our clientele are African-American riders, too. Our center is all about inclusion and giving everyone affordable opportunities to enjoy English riding.”

The center offers first-time horseback riding experiences and serves as a fun family, anniversary or date site in nature. It’s home to 31 horses — quarter, warmblood, Arabian and thoroughbred — in addition to a few ponies, goats, cats and dogs. “When you leave here,” said Leah, EEC’s professional dressage trainer, “you take the love of horses with you. That’s our goal throughout the region and state with every visitor.” Visit ellenwoodequestriancenter.org or call 404-317-2670 for more information.